Destination: To be able to back up a Git repository on a cloud-based Git service such as GitHub.

Motivation: One (of several) benefits of maintaining a copy of a repo on a cloud server: it acts as a safety net (e.g., against the folder becoming inaccessible due to a hardware fault).

Lesson plan:

→ Lesson: Remote Repositories covers that part.

→ Lesson: Preparing to use GitHub covers that part.

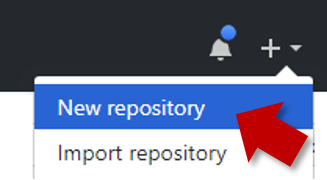

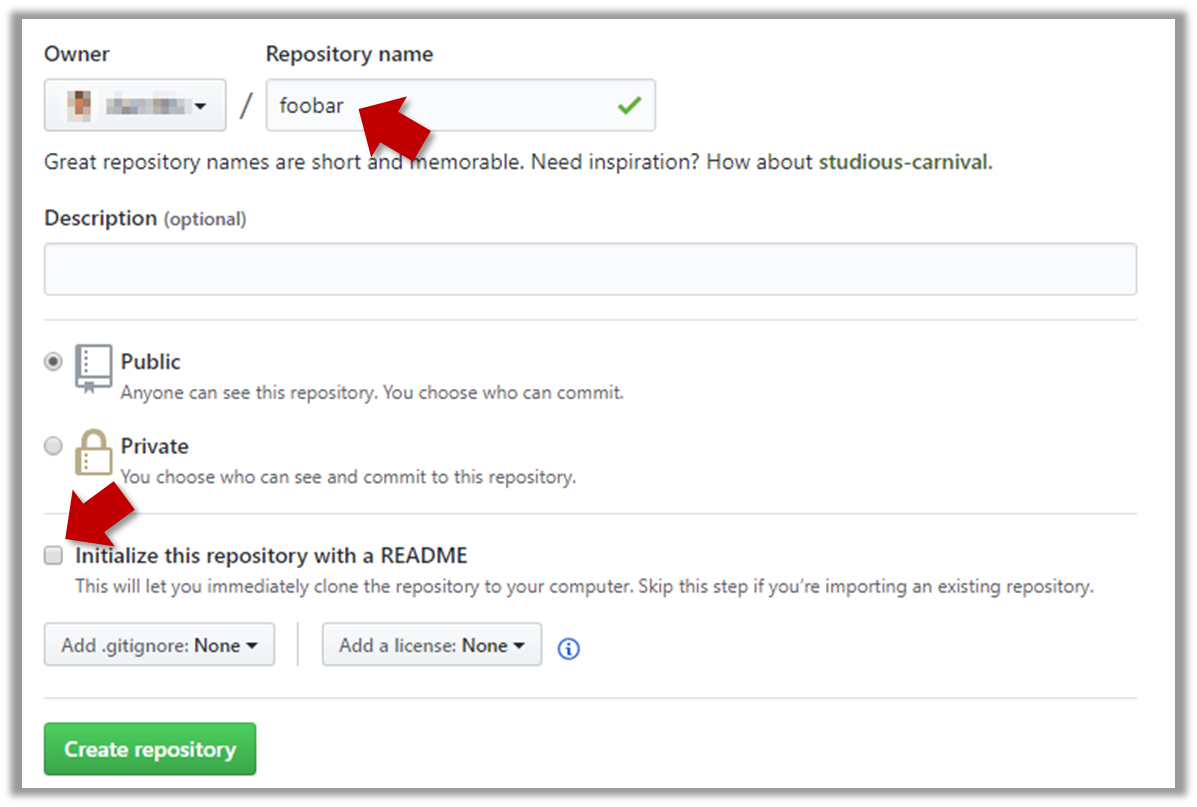

→ Lesson: Creating a Repo on GitHub covers that part.

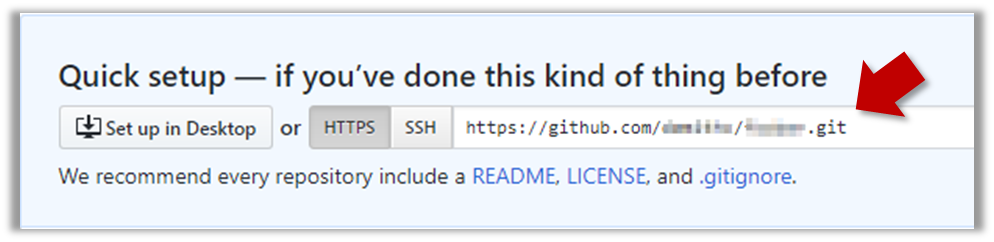

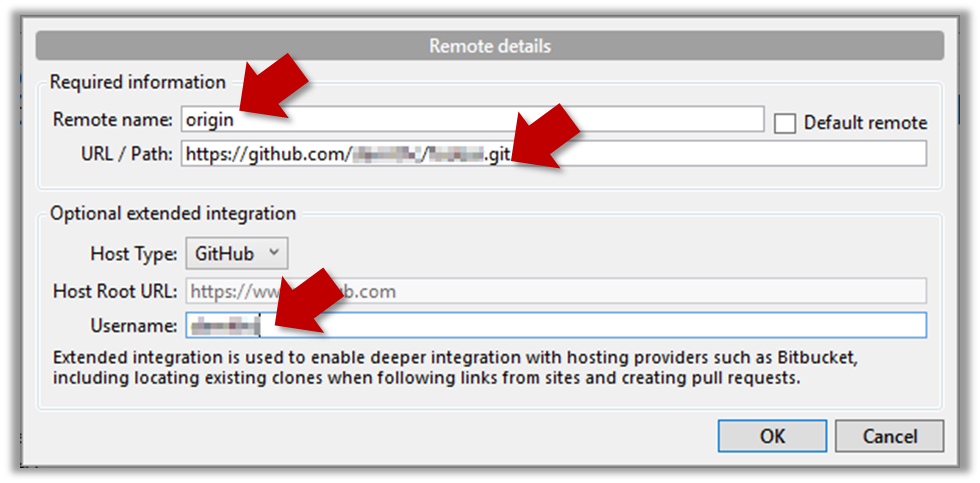

→ Lesson: Linking a Local Repo With a Remote Repo covers that part.

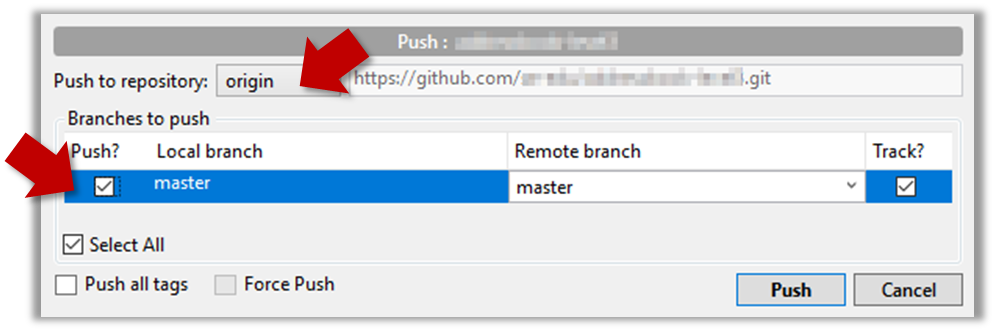

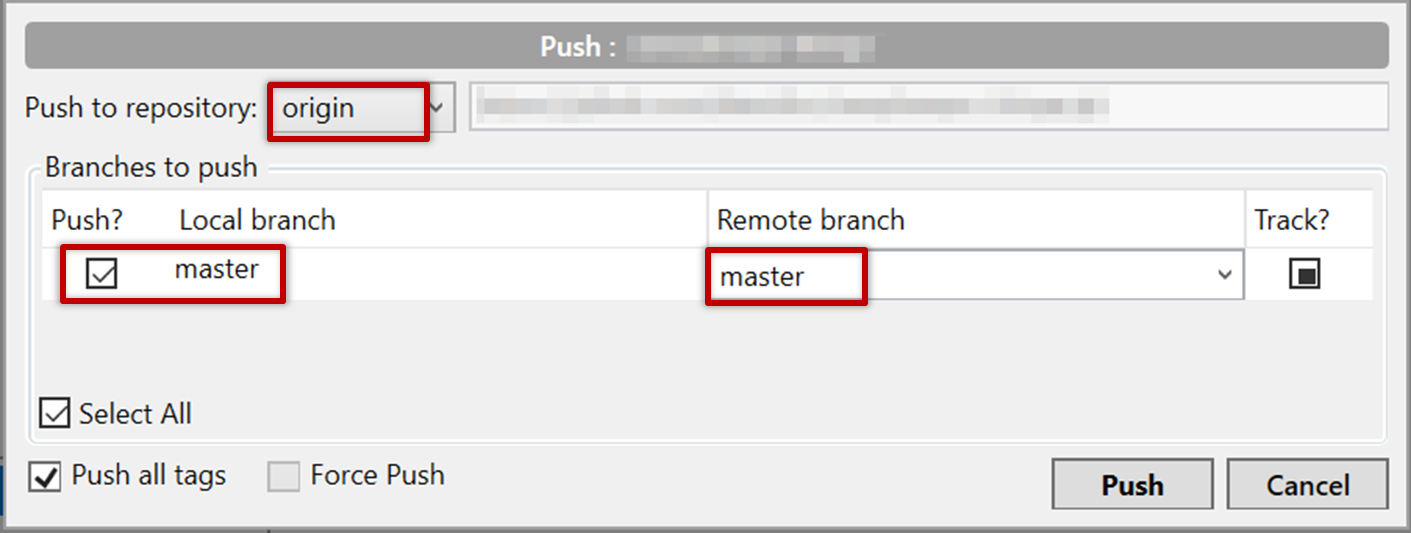

→ Lesson: Updating the Remote Repo covers that part.

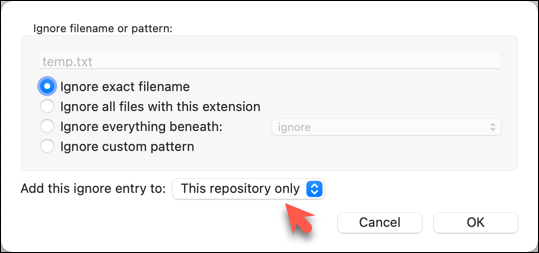

→ Lesson: Omitting files from revision control covers that part.

What you learned: You should now be able to creat a copy of your repo on GitHub, and keep it updated as you add more commits to your local repo. If something goes wrong with your local repo (e.g., disk crash), you can now recover the repo using the remote repo (this tour did not cover how exactly you can do that -- it will be covered in a future tour).

What's next: Tour 3: Using the Revision History of a Repo