Destination: ...

Motivation: ...

Lesson plan:

→ Lesson: Creating Branches covers that part.

→ Lesson: Merging Branches covers that part.

→ Lesson: Resolving Merge Conflicts covers that part.

...

Git supports branching, which allows you to do multiple parallel changes to the content of a repository.

First, let us learn how the repo looks like as you perform branching operations.

A Git branch is simply a named label pointing to a commit which moves forward automatically as you add more commits to that branch. The HEAD label indicates which branch you are on.

Git creates a branch named master (or main) by default. When you add a commit, it goes into the branch you are currently on, and the branch label (together with the HEAD label) moves to the new commit.

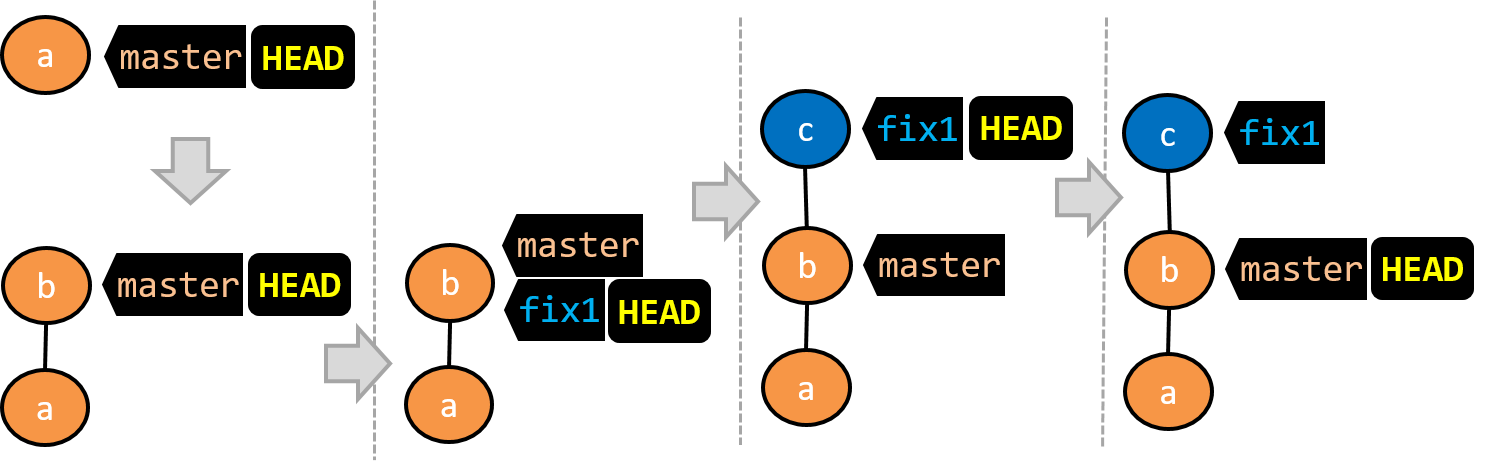

Given below is an illustration of how branch labels move as branches evolve. Refer to the text below it for explanations of each stage.

There is only one branch (i.e.,

master) and there is only one commit on it. TheHEADlabel is pointing to themasterbranch (as we are currently on that branch).To learn a bit more about how labels such as

masterandHEADwork, you can refer to this article.A new commit has been added. The

masterand theHEADlabels have moved to the new commit.A new branch

fix1has been added. The repo has switched to the new branch too (hence, theHEADlabel is attached to thefix1branch).A new commit (

c) has been added. The current branch labelfix1moves to the new commit, together with theHEADlabel.The repo has switched back to the

masterbranch. Hence, theHEADhas moved back tomasterbranch's .

At this point, the repo's working directory reflects the code at commitb(notc).

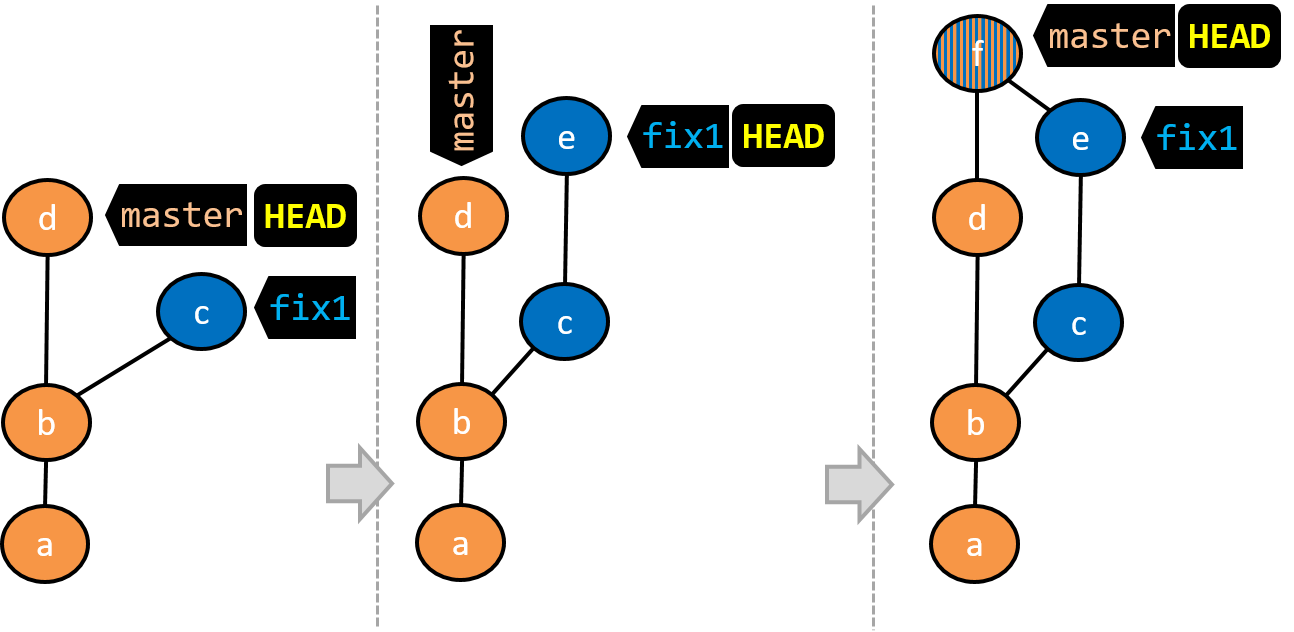

- A new commit (

d) has been added. Themasterand theHEADlabels have moved to that commit. - The repo has switched back to the

fix1branch and added a new commit (e) to it. - The repo has switched to the

masterbranch and thefix1branch has been merged into themasterbranch, creating a merge commitf. The repo is currently on themasterbranch.

Now that you have some idea how the repo will look like when branches are being used, let's follow the steps below to learn how to perform branching operations using Git. You can use any repo you have on your computer (e.g. a clone of the samplerepo-things) for this.

Note that how the revision graph appears (colors, positioning, orientation etc.) in your Git GUI varies based on the GUI you use, and might not match the exact diagrams given above.

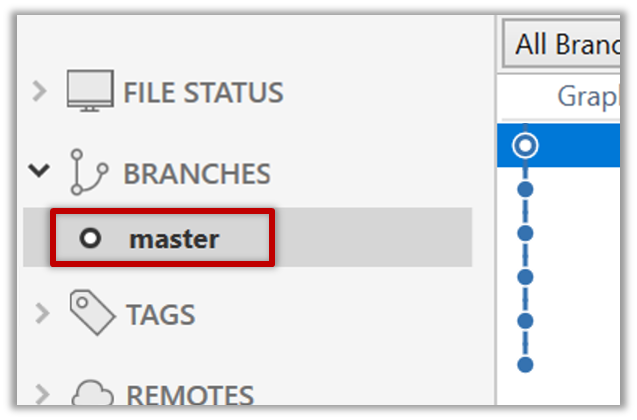

0. Observe that you are normally in the branch called master.

$ git status

on branch master

1. Start a branch named feature1 and switch to the new branch.

You can use the branch command to create a new branch and the checkout command to switch to a specific branch.

$ git branch feature1

$ git checkout feature1

One-step shortcut to create a branch and switch to it at the same time:

$ git checkout –b feature1

The new switch command

Git recently introduced a switch command that you can use instead of the checkout command given above.

To create a new branch and switch to it:

$ git branch feature1

$ git switch feature1

One-step shortcut:

$ git switch –c feature1

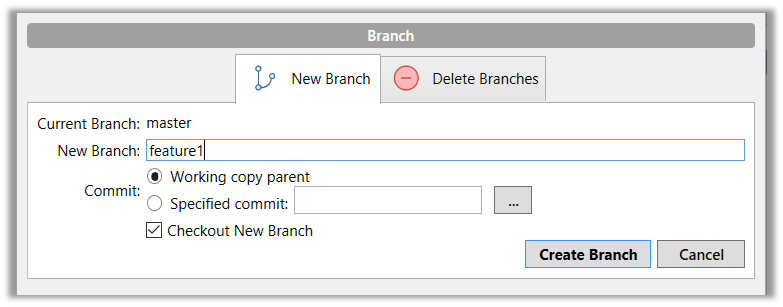

Click on the Branch button on the main menu. In the next dialog, enter the branch name and click Create Branch.

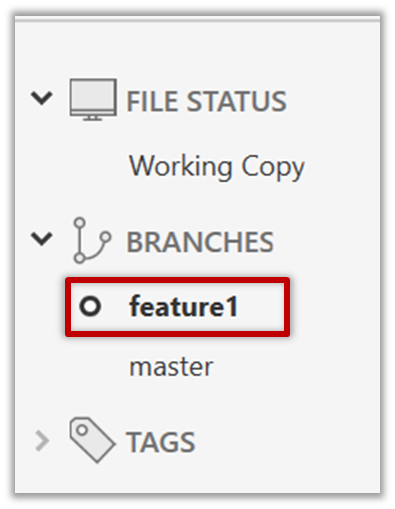

Note how the feature1 is indicated as the current branch (reason: Sourcetree automatically switches to the new branch when you create a new branch).

2. Create some commits in the new branch. Just commit as per normal. Commits you add while on a certain branch will become part of that branch.

Note how the master label and the HEAD label moves to the new commit (The HEAD label of the local repo is represented as in Sourcetree, as illustrated in the screenshot below).

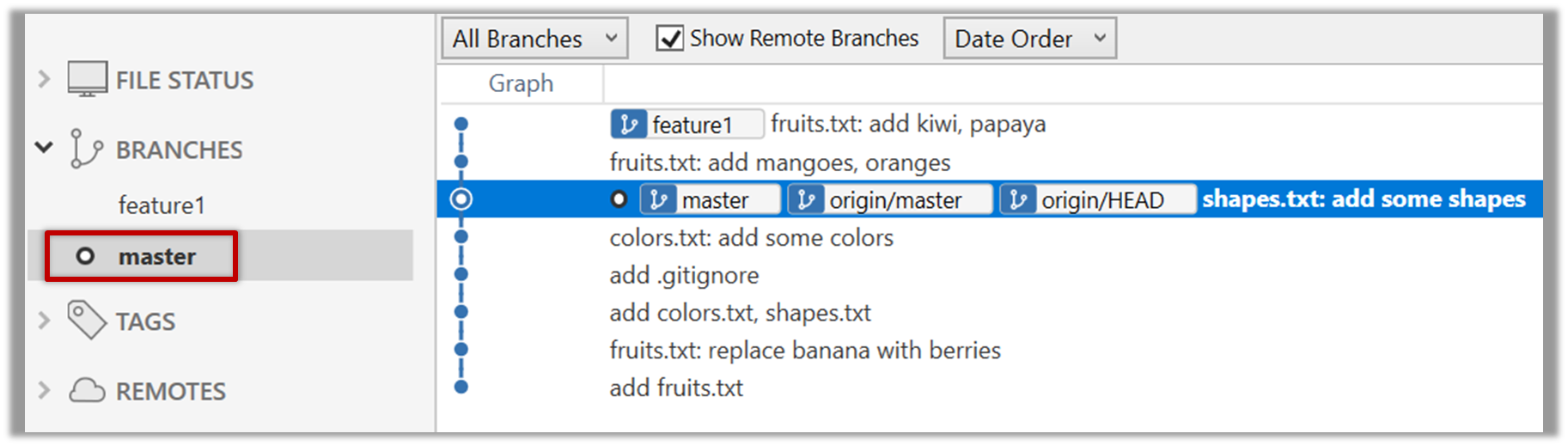

3. Switch to the master branch. Note how the changes you did in the feature1 branch are no longer in the working directory.

$ git checkout master

Double-click the master branch.

Revisiting master vs origin/master

In the screenshot above, you see a master label and a origin/master label for the same commit. The former identifies the of the local master branch while the latter identifies the tip of the master branch at the remote repo named origin. The fact that both labels point to the same commit means the local master branch and its remote counterpart are with each other.

Similarly, origin/HEAD label appearing against the same commit indicates that of the remote repo is pointing to this commit as well.

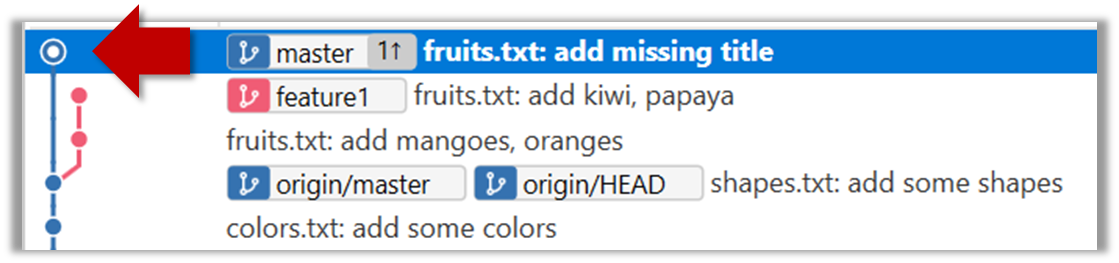

4. Add a commit to the master branch. Let’s imagine it’s a bug fix.

To keep things simple for the time being, this commit should not involve the same content that you changed in the feature1 branch. To be on the safe side, you can change an entirely different file in this commit.

5. Switch back to the feature1 branch (similar to step 3).

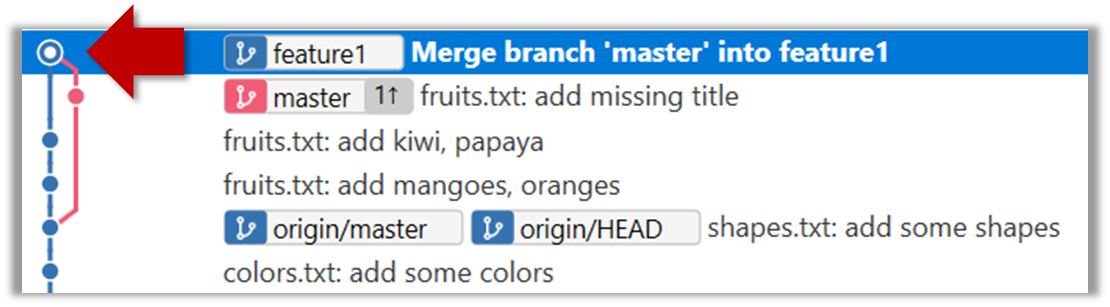

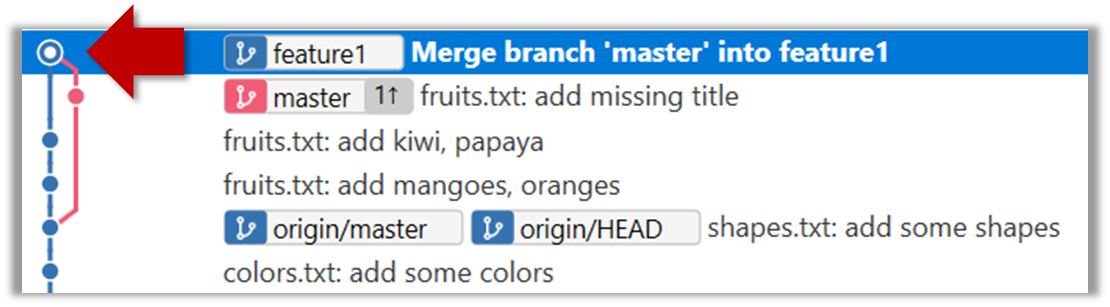

6. Merge the master branch to the feature1 branch, giving an end-result like the following. Also note how Git has created a merge commit.

$ git merge master

Right-click on the master branch and choose merge master into the current branch. Click OK in the next dialog.

The objective of that merge was to sync the feature1 branch with the master branch. Observe how the changes you did in the master branch (i.e. the imaginary bug fix) is now available even when you are in the feature1 branch.

To undo a merge,

- Ensure you are in the .

- Do a hard reset (similar to how you delete a commit) of that branch to the commit that would be the tip of that branch had you not done the offending merge.

In the example below, you merged master to feature1.

If you want to undo that merge,

- Ensure you are in the

feature1branch (because that's the branch that received the merge). - Reset the

feature1branch to the commit highlighted (in yellow) in the screenshot above (because that was the tip of thefeature1branch before you merged themasterbranch to it.

Instead of merging master to feature1, an alternative is to rebase the feature1 branch. However, rebasing is an advanced feature that requires modifying past commits. If you modify past commits that have been pushed to a remote repository, you'll have to force-push the modified commit to the remote repo in order to update the commits in it.

7. Add another commit to the feature1 branch.

8. Switch to the master branch and add one more commit.

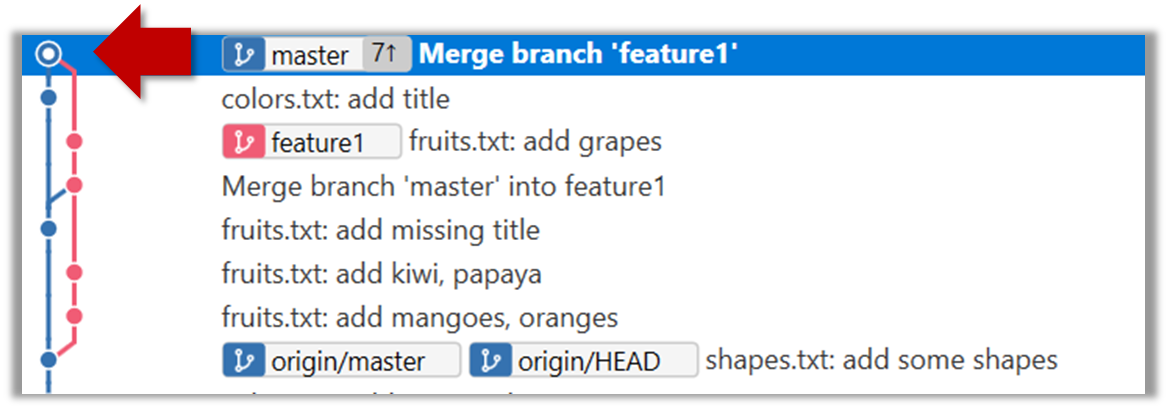

9. Merge feature1 to the master branch, giving and end-result like this:

$ git merge feature1

Right-click on the feature1 branch and choose Merge....

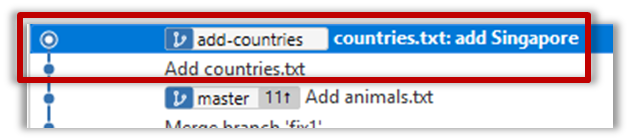

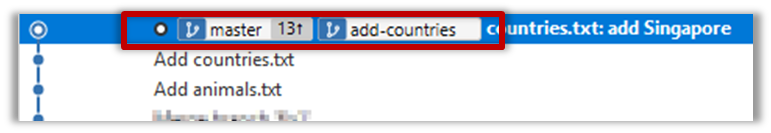

10. Create a new branch called add-countries, switch to it, and add some commits to it (similar to steps 1-2 above). You should have something like this now:

Avoid this rookie mistake!

Always remember to switch back to the master branch before creating a new branch. If not, your new branch will be created on top of the current branch.

11. Go back to the master branch and merge the add-countries branch onto the master branch (similar to steps 8-9 above). While you might expect to see something like the following,

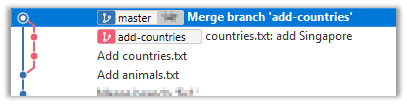

... you are likely to see something like this instead:

That is because Git does a fast forward merge if possible. Seeing that the master branch has not changed since you started the add-countries branch, Git has decided it is simpler to just put the commits of the add-countries branch in front of the master branch, without going into the trouble of creating an extra merge commit.

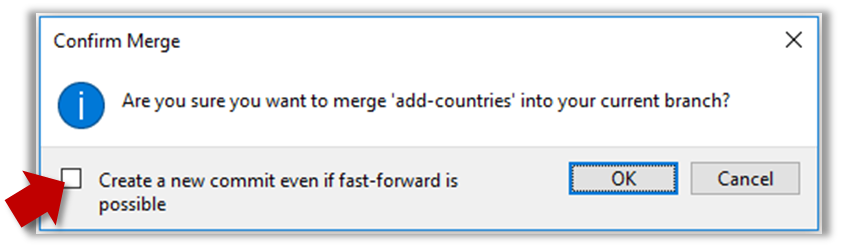

It is possible to force Git to create a merge commit even if fast forwarding is possible.

Use the --no-ff switch (short for no fast forward):

$ git merge --no-ff add-countries

Windows: Tick the box shown below when you merge a branch:

Mac:

- Go to Sourcetree

Settings. - Navigate to the

Gitsection. - Tick the box

Do not fast-forward when merging, always create commit.

...

Merge conflicts happen when you try to combine two incompatible versions (e.g., merging a branch to another but each branch changed the same part of the code in a different way).

Here are the steps to simulate a merge conflict and use it to learn how to resolve merge conflicts.

0. Create an empty repo or clone an existing repo, to be used for this activity.

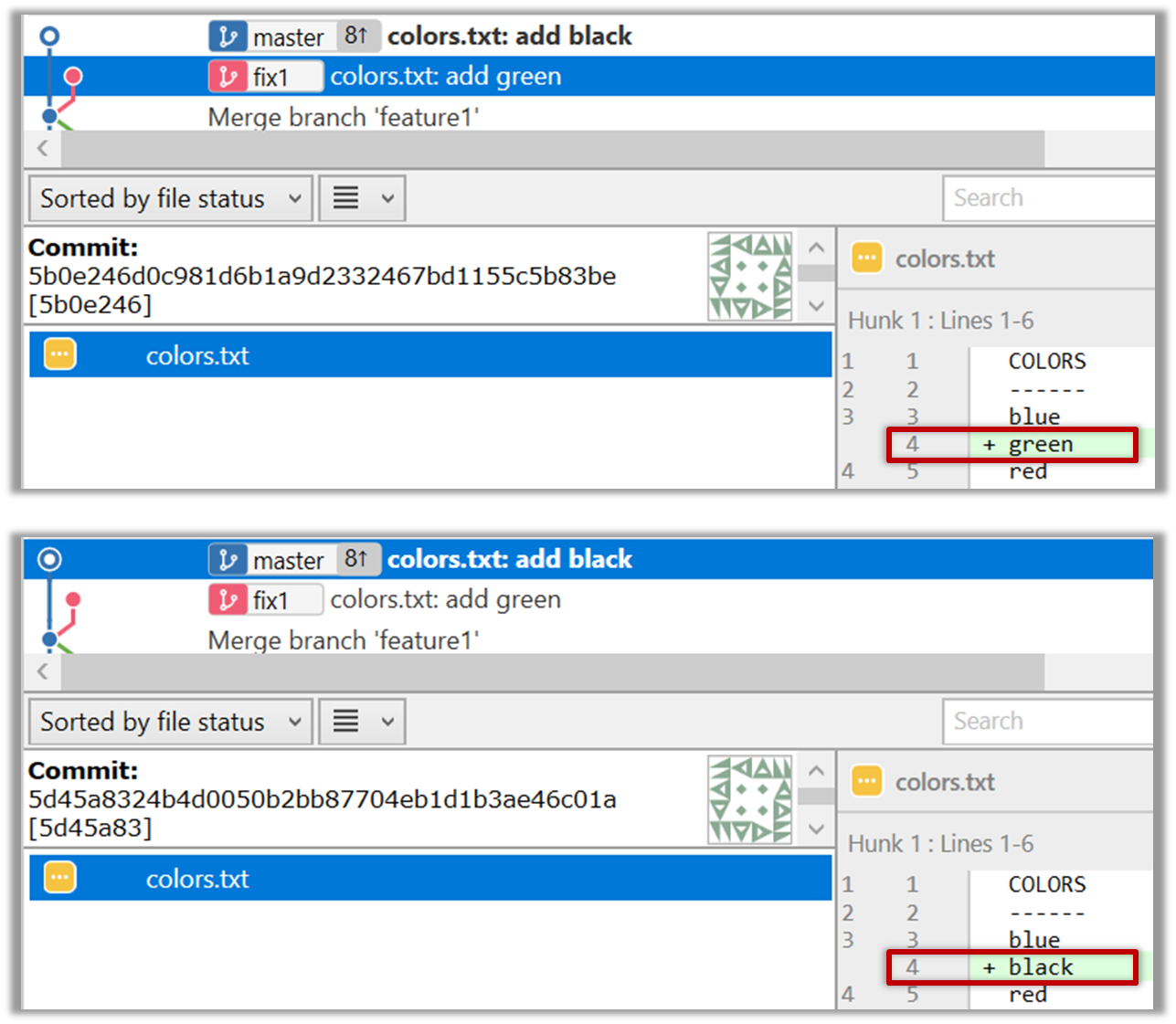

1. Start a branch named fix1 in the repo. Create a commit that adds a line with some text to one of the files.

2. Switch back to master branch. Create a commit with a conflicting change i.e. it adds a line with some different text in the exact location the previous line was added.

3. Try to merge the fix1 branch onto the master branch. Git will pause mid-way during the merge and report a merge conflict. If you open the conflicted file, you will see something like this:

COLORS

------

blue

<<<<<< HEAD

black

=======

green

>>>>>> fix1

red

white

4. Observe how the conflicted part is marked between a line starting with <<<<<< and a line starting with >>>>>>, separated by another line starting with =======.

Highlighted below is the conflicting part that is coming from the master branch:

blue

<<<<<< HEAD

black

=======

green

>>>>>> fix1

red

This is the conflicting part that is coming from the fix1 branch:

blue

<<<<<< HEAD

black

=======

green

>>>>>> fix1

red

5. Resolve the conflict by editing the file. Let us assume you want to keep both lines in the merged version. You can modify the file to be like this:

COLORS

------

blue

black

green

red

white

6. Stage the changes, and commit. You have now successfully resolved the merge conflict.

What you learned: ...

What's next: coming soon ...